Winter 2018

Published: 12/06/2017

Letter from the Chair

|

The leafless trees, cooler temperatures, and shorter days mark the opportunity to reflect on the past and envision the future. The last year marked the Department of Psychology’s 100th birthday, and the occasion to celebrate our growth from a faculty of two to a thriving department that has graduated over 25,000 undergraduate majors and 600 PhD students, and has generated over $2 billion in grant funding for our ground-breaking research. For me personally, I have the privilege of stepping into the Department Chair role, succeeding Professor Sheri Mizumori, who served as our leader for the last nine years. It is a great privilege to represent our talented students, faculty, and staff as we enter our second century.

When I think about our future, I envision a department whose scholarship will continue to provide critical insights into the mind, brain, and behavior, and will address the most important issues facing our region and the world. We will also arm our undergraduate students with the knowledge and skills they need to be successful in a wide variety of careers so they can go on to leave their mark on the world. Our graduate students will go on to be thought leaders in science, and their work will shape the future of academia, industry, clinical practice, and society more broadly.

The coming year brings exciting opportunities for our department. We welcomed our newest faculty member, Assistant Professor Noah Snyder-Mackler, who is featured in this newsletter. We are also hiring two new assistant professors this year, and our future will be in good hands with our growing cohort of the world’s most sought after junior faculty. With support from our friends, we have made investments in our students so they have opportunities to further grow intellectually in their time with us. This past year produced nearly $100,000 in endowment distributions and gifts that directly support our graduate and undergraduate students. Our two newest student endowments, The Aric Chandler Memorial Scholarship and the Fujita Family Fund will support their first recipients this year. You can learn more about our student support in this newsletter.

As state and federal funding is often precarious, we aim to build even stronger partnerships with our friends and alumni to advance our mission to promote healthy minds and society. Now more than ever, our community has the opportunity to promote ground-breaking research and help students realize their potential through philanthropic support.

All my best,

Cheryl Kaiser

Professor & Chair

Featured Articles

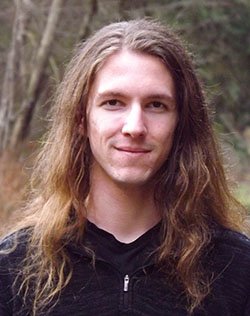

New Faculty Spotlight: Dr. Noah Snyder-Mackler

|

Recently we had a chance to sit down and interview our newest faculty member, Noah Snyder-Mackler, who is an Assistant Professor in the area of animal behavior. He joined the psychology department in the autumn of 2017.

How did you become interested in science and more specifically in animal behavior?

My whole life I’ve been fascinated by animal behavior — a fascination that, fortunately for me, has progressed from an avocation to a vocation (or perhaps some combination of both). I was exposed to science early in life being raised by two scientists. My mother is a sports rehabilitation scientist and my father was a neuroscientist. In addition, my grandfather is an avid amateur naturalist also had an early influence on me in terms of my interest in animal behavior. I was fortunate as a PhD student to be trained as a naturalist and mentored as an integrative animal behaviorist by two premier animal behavior researchers (Dorothy Cheney and Robert Seyfarth) at the University of Pennsylvania where I combined behavioral observations with genetic analyses to study the evolution of sociality in cowbirds and gelada monkeys. After that, I went to Duke University for a postdoc where I worked with evolutionary biologist Jenny Tung and honed my genomics skills studying how our social environment directly affects our immune system.

What draws you to your work? Why are you passionate about it?

We still don’t know how the social environment “gets under the skin” to alter physiology and impact health, survival, and reproduction in social animals. When I’m wearing my animal behaviorist hat, I’m study the interaction between the social environment and individual behaviors to see how these behaviors have ultimately been shaped by natural selection. When I’m wearing my biopsychologist hat, I am using my study subjects (monkeys) as a model for humans — after all, we’re all primates! Most of the time I’m wearing both hats — drawing on my insights from behavioral ecology to gain a better understanding of human behavior and health.

Your work involves field research which can be exciting and challenging. Do you have a favorite field site where you conduct your primate research?

I conduct research at two field sites, which are very different from one another. The most comfortable of the two is Cayo Santiago, which is a small island off of the southeastern coast of Puerto Rico and home to a colony of over 1000 free-ranging rhesus macaques. This field station is maintained by the Caribbean Primate Research Center and the University of Puerto Rico. We can conduct our research on Cayo Santiago and then motor our way back to the main island of Puerto Rico each night. Cayo Santiago was unfortunately heavily damaged by Hurricane Maria, but we're gradually rebuilding infrastructure there. My other field site, where I study gelada monkeys, is in the highlands of Ethiopia – a much more remote and challenging site. Despite the limited communication and logistical nightmare of getting supplies to and from the campsite, this field site is my favorite. The amazing landscape and unique animals make it one of the most beautiful places in the world.

Why is your lab’s research important? Why should the community care?

The one sentence cocktail party description of my work is “I study why chronic psychosocial stress is bad for your health and how having good friends can help protect you from those negative consequences”. That’s typically well-received, but it is often followed by the inevitable question: “So why aren’t you studying humans?” The short answer is that the social animals that I (and others) study make for a simpler model of human social behavior because, while we share many core neural and genetic pathways with nonhuman primates, they don’t have some of the added complications of human culture (e.g., monkeys don’t smoke, drink, or do drugs). The ultimate goal is of my lab’s work to identify underlying mechanisms so we can help people live longer, healthier lives.

Aric Chandler Memorial Scholarship

"Anything is possible when we surpass our fears. The true beauty of life can only be realized when we learn to push our boundaries. And all it takes is a simple change in perspective."

- Aric Chandler

|

Aric Chandler had a passion for life and a deep desire to help young people overcome their struggles to reach their full potential. Aric had a dream to begin his journey toward that goal as a psychology major at the University of Washington. On August 4, 2016, that dream was cut short. Just days after being admitted to UW as a transfer student from Bellevue College, Aric died unexpectedly from SUDEP (Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy), which takes the lives of 2,000-3,000 people each year in the United States. What did not die that sad day was Aric's passion and commitment to working with adolescents. Aric's parents, David and Kacee Chandler, along with his family members and friends, established an endowment to keep Aric's dream alive by providing support for transfer psychology majors who plan to work with children and adolescents.

Aric's family and friends are extremely proud of his ability to overcome obstacles and of the kind and generous young man he had become. "Because Aric overcame his own difficult struggles with anxiety as a teenager, his passion was helping young people overcome their challenges and fulfill their life's potential," said David Chandler, who continued, "this endowed scholarship will help dozens of psychology students continue Aric's life's work and passion, who will in turn impact the lives of thousands of young people in our lifetimes and beyond." Because Aric was set to transfer to UW from Bellevue College, his family and friends chose to establish a scholarship that would directly benefit psychology majors who entered UW from Washington community colleges. These community colleges often help people who have tremendous potential but may not be ready nor have the financial means to attend a four-year university.

|

This fall, the psychology department offered the first Aric Chandler Memorial Scholarship. Nearly fifty psychology majors applied for the single award of $4,000. Applicants were asked to demonstrate their interest in child or adolescent psychology by outlining their relevant volunteer, research, work, or personal experiences, as well as their educational and career goals. The recipient of the inaugural Aric Chandler Memorial Scholarship is psychology senior Sunny Allen.

Sunny transferred to UW from Seattle Central College. A full time student, Sunny recently served as a peer mentor for the Psychology Department's Transfer Academic Community (TRAC) class, which helps first quarter transfer students find their academic home and build community within the psychology major. Looking forward, she hopes to work with children and adolescents in the area of treatment and diagnosis of ADHD. "I want to be an advocate for children and teens and work to reverse the effects of implicit bias that begin early in life," says Sunny. Refecting on being the inaugural recipient of this scholarship, Sunny continues, "I am so grateful and honored to receive the Chandler Award this year and I hope to carry on Aric Chandler's vision by helping disadvantaged children realize their potential and achieve their goals."

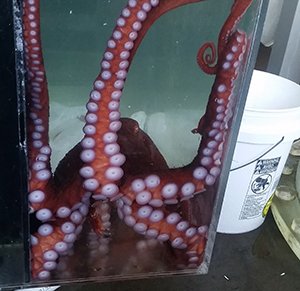

Across the Evolutionary Divide: the Story of Gaia

|

| Dominic Sivitilli |

Dominic Sivitilli (Behavioral Neuroscience student with David Gire) spent the summer in Friday Harbor Laboratories in the San Juan Islands studying Enteroctopus dofleini, the giant Pacific octopus. Check out his account of his experience here.

Vertebrates make up but a small minority of the diversity that evolution has made of the ancestral nervous system. If we truly mean to understand cognition, we need to broaden our perspective across the diversity of these forms—we need to look beyond the vertebrate model to other worlds of thought entirely. For this reason, I have chosen the octopus as my model organism.

I laid the groundwork for studying cognition in this new model by consolidating a paradigm to deconstruct and characterize the behavior of Octopus rubescens, the Pacific red octopus, the smaller of the two species local to the Puget Sound (at an adult arm span of around 30 cm). After a year, I was ready to turn my sights on Friday Harbor Laboratories in the San Juan Islands, and to the other species, Enteroctopus dofleini, commonly known as the giant Pacific octopus, the largest species of octopus known.

I spent weeks diving the dark, green depths that wove between the San Juan Islands; on the edge of black, watery gulfs I searched for a long lost cousin. 45 feet below San Juan County Park, my dive team at last methodically encircled a large, camouflaged, breathing mass, as it watched us intently.

Like a fission reaction, word spread of our new lab resident. Before I could catch my breath, a wave of curious and confused descended on Lab 2.

|

Nightfall and finally alone in a quiet, dim lab, I felt my movements being watched. I sat facing my new model, observing her as she continued to fix her gaze upon me. About five feet separated the tips of her opposite arms when she reached them outward—she was young, yet, she seemed so old, reaching out to me from deep evolutionary time.

Unlike the highly centralized nervous system of the vertebrates, that of the octopus exists mostly in their eight flexible arms. Here, in each arm, the nervous system takes the form of a chain of neural clusters, or ganglia, running in parallel to the octopus’ suckers, with each ganglion processing the input from the tens of thousands of sensory receptors from the adjacent sucker. By outsourcing a large degree of motor and sensory processing into localized semi-autonomous neural pathways within these chains, the octopus can process this massive amount of sensory information in parallel while relieving the brain of much of the necessary computational burden to respond accordingly.

When an arm is removed or its connection to the brain severed, it will move freely, respond to touch and recoil from noxious stimuli. This autonomous behavior suggests that the arms are inhibited when attached to the brain, and by selectively removing inhibition of certain peripheral neural pathways, the brain allows the arms to execute behaviors while the other pathways within the arms remain silenced. The large degree of information from the suckers is then consulted to adjust the automated motor response to the immediate and acute representation of the world.

This being before me took a different path entirely to a wholly foreign mind, a journey that began when we parted more than 500 million years ago: two simple-minded cousins setting out to wander aimlessly a long, turbulent road toward cognitive complexity. I named her Gaia.

As I prepared her next tank for her arrival, Gaia was visited regularly by lab residents and visitors alike. Although obviously too small for comfort, her temporary tank allowed the opportunity for visitors to easily interact with her. To the unnerving realization of the uninitiated, even the most gentle contact with her suckers was enough to elicit her arm to ensnare and eagerly coil around idle hands. The more one was to resist, the more eager the arm was to entangle its newly found play-thing, while each sucker searched intently for a relevant stimulus to communicate to the brain.

|

She was placed in her new, larger tank and set out immediately to explore its boundaries. Typically, studies of animal behavior employ an ethogram, an exhaustive list of an animal’s behavior. Instead, an automated approach allows me to catalogue not just the behavioral profiles of the entire animal, but that of each arm simultaneously. By then characterizing correlations in movement pattern and symmetry between arms as a function of the sensory information available to the octopus, I can begin to model the flow of information in this system that allows the octopus to coordinate its highly autonomous arms in response to controlled exposure to various environmental conditions, revealing the computational strategies they are employing to coordinate the highly independent divisions of their nervous system. Before, I could only accomplish this with the Pacific red octopus fitting comfortably in a 50 gallon tank. Friday Harbor Labs allowed me to work at a different scale entirely.

Gaia continued to attract the attention of the multitude of residents and visitors during the summer terms of the labs, while I and the occasional team of volunteers, to whom I owe an incredible debt of gratitude, provided enrichment, cleaning service, and a daily sacrificial crab.

After many came to visit her one last time, we returned Gaia to her home below San Juan County Park six weeks after we found her. I then bid farewell to the labs, and the wonderful and welcoming community that I called home for the summer of 2017.

Perceptive, curious, and above all, distant, Gaia manifested everything to me that makes the octopus model so attractive. Two cousins we are, meeting across the evolutionary divide of over 500 million years.

Support a Psychology Student Through Huskies@Work

Calling all Psychology alum: now you can help a student with Huskies@Work, UW Alumni Association’s job shadowing program.

Psychology is one of the most dynamic majors on campus: with a degree under their belt, students can pursue careers in research, therapy, business, community health, technology, and many other fields. As an alum, you can play a part in their path to choosing a career by showing them what can be possible after graduation.

Huskies@Work is offered twice each year, during one month in the fall and one month in the spring. Alumni and students fill out applications and are matched based on career field and interests. You’ll get the chance to share a day in your life. From meetings to site visits, informational coffees to meetings over Skype or phone call — you can show a fellow Dawg what it’s like to walk in your shoes.

Spring 2018 applications open in early 2018. Learn more and get involved today on the Huskies@Work website.

Looking for more ways to connect with UW Psychology post-grad and beyond? Visit the department website and stay connected with us today.